YELLOW FEVER

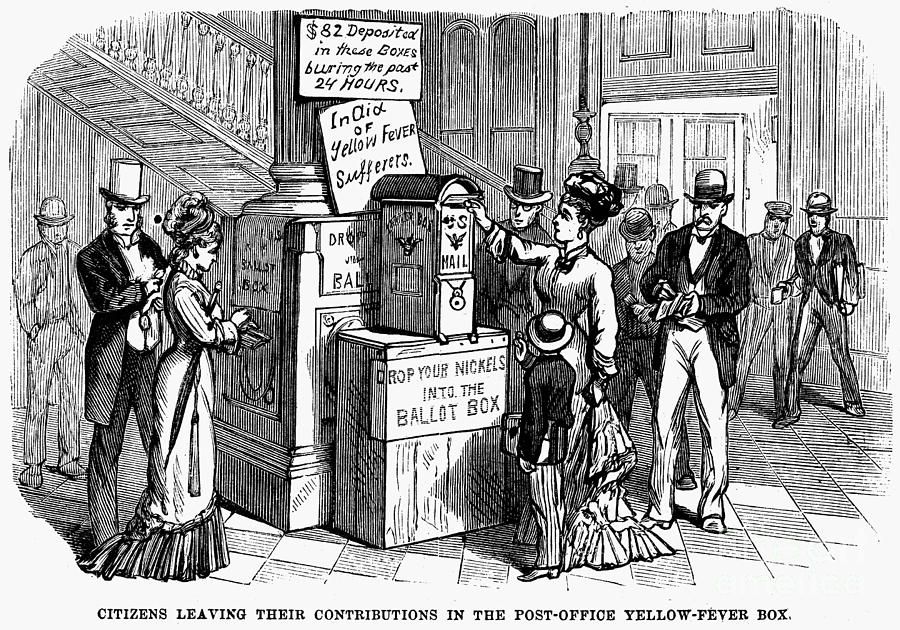

(Transcribed from: History of Alabama and dictionary of Alabama biography, Volume 2 Thomas McAdory Owen, Marie Bankhead Owen)

Alabama was first visited by this dread scourge in 1704, when a vessel from Santo Domingo brought the disease to Fort Louis de la Mobile, then the chief town of French Louisiana, and barely two years following settlement. The trouble assumed epidemic proportions, and among those who succumbed was Henri de Tonti.

Since that date there have been many visitations to this and other towns in the State. In 1873, the disease reached the town of Huntsville in the Tennessee Valley.

Henri de Tonti was an Italian soldier, explorer, and fur trader in the service of France In 1702, at Old Mobile, he was chosen by Iberville as an ambassador to the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes and conducted several negotiations (Wikipedia)

Henri de Tonti was an Italian soldier, explorer, and fur trader in the service of France In 1702, at Old Mobile, he was chosen by Iberville as an ambassador to the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes and conducted several negotiations (Wikipedia)

First epidemics were first traced to the West Indies

Yellow fever has never been known to originate in the United States, and all epidemics have been traceable to the West Indies where, up to a few years since, it existed throughout the year. The first recorded epidemic in the history of the world occurred in December, 1493, in Santo Domingo, at the town of Isabella, which had been only that month founded by Columbus, during his second voyage to America.

Cause of the spread of the disease was discovered

Since the occupation of Cuba in 1899 by the United States, when the cause of the spread of the disease was ascertained, and Havana and other towns were cleaned up by William Gorgas,1 there was no recurrence of yellow fever in Alabama except in sporadic cases. The last reported cases were in 1905, when it manifested itself at Castleberry, at Montgomery and on board a vessel in Mobile Harbor. The subjects at Castleberry and Montgomery were refugees from Mobile.

Quarantines were important

Effective quarantine regulations have in a large measure been responsible for the arrest of the trouble in recent years, the United States Public Health Service having been very strict in its enforcement.

A survey shows the mortality rate at Mobile in all epidemics to be high. This is accounted for principally from the fact of laxity by municipal authorities in the enforcement of preventive measures and quarantines during the early days of the epidemics.

The suppression of facts in reference to the prevalence of the disease has also contributed to its spread. Even as late as 1899 the State health authorities were severely criticized for reporting the disease immediately after it manifested itself, it being felt that injury in a financial way was done by circulating the information.

Traceable to refugees from the Gulf Coast

Prevalence of the disease in other towns in the State is traceable to refugees from Mobile, New Orleans, or Pensacola in all cases. Prior to the discovery of the mosquito theory in 1899, no cleanup campaign had ever been waged, and practically no preventative efforts were used except disinfectants, the popular theory being that the coming of the first frost was the only means of arresting the trouble.

Statistics show that the large per cent of deaths was among refugees who returned to the infected districts after the first frost, contracted the fever and died. Many cases among African Americans have been reported, but the percentage of deaths among them has always been small.

Years of severe yellow fever outbreaks in Alabama

Statistics.—Below will be found statistics of recurrence, cases, deaths, periods covered and other items of importance. For early years but few facts are available, although there can be hardly any doubt that the mortality of the early colonists in the eighteenth century is to be traced to the scourge of yellow fever.

- 1704. Severe epidemic among the then small colony at Mobile, introduced from Santo Domingo. Many deaths, but no available statistics.

- 1765, 1766. In each year severe epidemics at Mobile, introduced from Jamaica. The fatalities were largely among newcomers, or late arrivals.

- 1805. Few deaths at Mobile. Disease introduced from Havana.

- 1819. Severe epidemic at Mobile from August 19 to November 30, with 274 deaths. Many cases occurred after frost. Epidemic at Fort St. Stephens from July 4 to December 1; and at Fort Claiborne July 4 to December 1. Introduced from Havana.

- 1821. Sporadic cases; and seven deaths in Mobile during October. Other points not affected.

- 1822. Severe epidemic at Blakely. “Only four or five cases” reported at Mobile.

- 1824. Six deaths in Mobile, the last September 25, more than a month before frost.

- 1825. Severe epidemic at Mobile. The board of health concealed the true conditions, and although the disease made its appearance as early as July, no official report was given out until September 2, when only one case was announced. It was not until September 11 that official admission of epidemic conditions was made. Many deaths reported.

- 1826-27. Sporadic cases in Mobile in September.

- 1828. Mild epidemic in Mobile, but no statistics available.

- 1829. Epidemic in Mobile; 130 deaths. First case August 14.

- 1837. Four cases appeared September 20 at Mobile, but no more at that time. On October 2 a frost fell and those who had left the city returned. On October 10, cases broke out in every section of the city, and the disease was soon epidemic, running to the end of November, 350 deaths reported.

- 1838. Few sporadic cases at Mobile.

- 1839. Severe epidemic at Mobile among the new inhabitants. The first case occurred August 11, and the last case October 20. Deaths, 450.

- 1841. A few scattering cases among inhabitants of the interior, then visiting in Mobile.

- 1842. Slight epidemic in the southern section of Mobile; 160 cases, and 70 deaths.

- 1843. Severe epidemic at Mobile. First case reported August 24, and the last, November 5. The public was kept in ignorance, the disease became widespread. Cases 1,350, with 750 deaths. The infection was traced to New Orleans.

- 1844. Epidemic at Mobile. The first case reported August 14. Deaths, 40.

- 1845. Few cases at Mobile, though it did not manifest itself until November 9. Only 1 death.

- 1846. Four deaths at Mobile. The first case appeared September 11.

- 1847. Epidemic at Mobile. The first case, August 2. Deaths, 78.

- 1848. Mild epidemic at Mobile. The first case August 18. Deaths, 24.

- 1849. Mild epidemic, the first manifestation, July 3. Deaths, 21.

- 1851. Mild epidemic at Mobile. No records kept.

- 1852. Epidemic in Selma, now known to have been infected by steamboat from Mobile, although there is no reported occurrence of the disease for that year in the latter. First reported case and death, September 1, and the last death, November 13. Deaths, 53.

- 1853. Epidemics in Mobile, Montgomery, Demopolis, Cahawba, Fulton, Hollywood, Porterville, St. Stephens Road, Bladen Springs, Spring Hill, Dog River Factory and Citronelle.Mobile was infected from the bark Milliades, from New Orleans; and other points by refugees from Mobile, except Hollywood which was infected from New Orleans.Of the 25,000 population in Mobile, 8,000 left the city. First case and death July 11, the last case December 16. Total deaths, 1,191. A large number of cases among negroes, but only 50 died.In Montgomery the first case appeared in September, and last in November. Deaths, 35.The epidemic at Spring Hill was largely among refugees; 50 out of a group of 60 were attacked, the death rate being 5 whites, 2 mulattoes and 1 negro.No record was kept of the cases and deaths at Cahawba, Citronelle, Demopolis, Fulton and St. Stephen’s Road.At Porterville, there were no cases among the inhabitants, but 5 cases with 2 deaths among refugees.At Hollywood the first case developed, August 15, and the last September 20, with 10 cases and 6 deaths. Infection from New Orleans.

At Dog River out of a population of 300, there were 69 cases with 23 deaths; the first case, August 18.

This epidemic was the most widespread which had occurred up to that time, not only in Alabama, but over the entire country.

- 1854. Epidemic at Montgomery, with a few sporadic cases at Mobile. Deaths in Montgomery, 45, the disease running from September to November.

- 1855. Epidemic at Montgomery, September to November. 30 deaths.

- 1858. Epidemic at Mobile. Deaths, 70; the first case, August 3.

- 1863, 1864. Few sporadic cases at Mobile during these years, brought in by blockade runners from Key West and from the West Indies. In 1863, 2 deaths reported with S in 1864.

- 1867. Epidemic in Mobile, with a few sporadic cases in Montgomery, and also at Fort Morgan. The disease appeared at all three places August 13. No statistics are available; but infection from New Orleans.

- 1870. Sporadic cases at Montgomery and Whiting, with a mild epidemic at Mobile. Cases at Montgomery, August 22 to November 19; at Mobile, August 27 to November 19; and among refugees at Whiting about the same period. Infection was from Havana.

- 1873. Severe epidemics occurred throughout the entire Gulf States. Mobile, Montgomery, Junction, Huntsville, Oakfleld and Pollard were visited.At Mobile infection was traced to New Orleans; occurrence from August 21 to November 29. Total of 210 cases, with 35 deaths.Montgomery was infected from Pensacola, the first case reported, August 27. The whole population of the city, except about 1,800 fled. There were 500 cases, with 108 deaths. The last case appeared November 10.The first case at Oakfleld reported September 22. Total of 7 cases, with 1 death.Sporadic cases at Pollard, but no statistics available.In a population of 35 at Junction, there were 22 cases, with 14 deaths.At Huntsville there were 3 cases, with 1 death.While Memphis and Shreveport had many more cases than New Orleans and Mobile in this epidemic, the mortality rate in the latter was much greater.

- 1874. Epidemic at Pollard. Infection brought from Pensacola. No statistics.

- 1875. Mild epidemic at Mobile; the first case reported September 1, the last October 20. Cases 16, with 8 deaths. Some cases occurred among refugees from Mobile to Whiting.

- 1876. Two cases, one a refugee from New Orleans, the other a refugee from Savannah, developed in the Battle House. The one from New Orleans died.

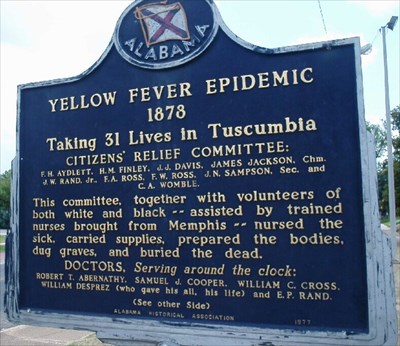

- 1878. Severe epidemics in the Tennessee valley, with infection in most cases from Memphis. There were cases at Athens, Courtland, Decatur, Florence, Huntsville, Leighton, Stevenson, Town Creek, Tuscumbia and Tuscaloosa. Spring Hill, Whistler and Mobile in the southern part of the State were visited.Athens had 2 cases, with 2 deaths; Courtland, one case with one death; Decatur 187 cases, 51 deaths; Florence 1,409 cases, 50 deaths; Huntsville 33 cases, 13 deaths, none of these being resident cases; Leighton, 4 cases, 1 death; Mobile 297 cases, 83 deaths; Spring Hill, 1 death among the refugees, no local cases; Stevenson 11 cases, and 6 deaths, first case on September 1; Town Creek, 4 deaths; Tuscaloosa 2 cases, 2 deaths; Tuscumbia 97 cases, 31 deaths; Whistler several cases among refugees, 1 death only, inhabitants not attacked.The epidemic of this year was general over the entire Mississippi Valley, as far north as Cairo, Ill. Many cases in the north Alabama towns were refugees from other points. In only a few cases were the natives affected. The infection in Mobile was from Biloxi, Miss., the first case showing early in August. Most of the cases were in the southern section of the town. The last death, October 30; a slight frost had fallen October 23.

- 1880. One case developed on board a vessel from Havana, then in Mobile Harbor. No cases in the city.

- 1883. Severe epidemic at Brewton; the first case, September 12, the last, November 6; 70 cases, 28 deaths. The presence of yellow fever was never admitted by the local physicians, but it was so pronounced by the U. S. Marine Health Service and the State health officer.

- 1888. Outbreak at Decatur, in which there were 10 cases and 1 death; the first case, September 4. Nearly the’whole population of the town fled.

- 1893. Two cases, with one death at Fort Morgan.

- 1897. The outbreak of this year was widespread, cases occurring at Alco, Bay Minette, Flomaton, Greensboro, Mobile, Montgomery, Notasulga, Selma, Sandy Ridge and Wagar. Alco, 1 case, no death; Bay Minette, 1 case, 1 death; Flomaton, 98 cases, 5 deaths; Greensboro, 1 case, 1 death; Mobile, infected from Ocean Springs, Miss., 361 cases, 48 deaths; Montgomery, 120 cases, 11 deaths; the epidemic lasting from October 18 to November 10; Notasulga, 1 case, no deaths; Selma, 12 cases, 2 deaths, epidemic lasting from October 23 to October 31; Sandy Ridge, 1 case, no death; Wagar, 45 cases, 3 deaths.

- 1903. One case and death at Mobile.

- 1905. Cases at Castleberry, Mobile quarantine station, and Montgomery. Two cases and two deaths occurred at Castleberry. The case at Montgomery was a refugee.

1William Gorgas, an Alabamian is credited with cleaning up mosquito breeding grounds which spread yellow fever.

Start researching your family genealogy research in minutes for FREE! This Ebook has simple instructions on where to start. Download WHERE DO I START? Hints and Tips for Beginning Genealogists with On-line resources to your computer immediately with the a FREE APP below and begin your research today!

Reviews

“This book was very informative and at a very modest price. One web site I may have missed in your book that has been very helpful to me is genealogybank.com. I found articles about several of my ancestors in their newspaper archives. Thank you for your great newsletter and this book.”

“The book was clear & concise, with excellent information for beginners. As an experienced genealogist, I enjoyed the chapter with lists of interview questions. I’d recommend this book to those who are just beginning to work on their genealogies. For more experienced genealogists, it provides a nice refresher.”

My 3 Great Grandmother and two adult sons are said have died in a Yellow Fever epidemic that occurred in the Cahaba Valley area of Shelby County in the summer of 1835. I find no listings for that epidemic anywhere. Does anyone have information about it or have even heard of it?

Yes My family lived in Lowndesboro and te Bonnell Family lost 6 children. Tomorrow there will be a program t the Alabama Department of Archives and History with a program about Mobile physician Joseph C. Nott who established Medical Association of the State of Alabama and took a took a leading role in the creation of a stte medical school in Mobile. Yellow Fever killed 4 of his children, I found this information on the site of the Alabama Department of Archives and history ‘ Press Release: Food For Thought ,”

Eric Peterson discusses presents “Nott, Our Doctor: How Medicine,Race Religion and Evolution Colide. This lecture will be presented September 20 by Erik Peterson. Some of my ancestors, too lost 5 children to Yellow Fever in Lowndesboro, and their father and mother and 1 surviving child moved from their hoe on the Alabama River to higher ground in Lowndesboro, leaving an area on the River where more mosquitoes were present.

That the third thing that I couldn’t get to load, something about the link.

[…] Trains did not run […]

This was great reading thanks

Awesome reading Thanks

My sister had yellow fever when she was young,but it doesn’t say none about this fever in the 1980s??? Is this possible because my mom told me this and I remember my sister being really sick. She couldn’t walk.