Did you know the Revolutionary War was fought in Alabama?

This story is an excerpt from the book ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Exploration: Lost & Forgotten Stories (Volume 1

When the American Revolution comes to mind, most people think of the Eastern seaboard but the war raged from Georgia north to Maine.

Fort Louis de la Mobile

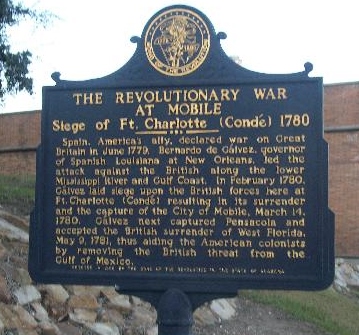

Battle of Fort Charlotte

It may be surprising, to know that a Revolutionary War battle took place in the heart of what is now downtown Mobile, Alabama. “The Battle of Fort Charlotte was fought from March 10-13, 1780 for control of a sixty-year-old fort on the waterfront of the former French city. It was one of two significant Alabama battles of the Revolution and opened the door for the most significant British defeat on the Gulf Coast,” I Remembered today as the Battle of Fort Charlotte, the engagement was an important part of General Bernardo de Galvez’ Gulf Coast campaign.

Fort Conde, located in Mobile, Alabama, at 150 South Royal Street, is a reconstruction, at 4/5 scale, as a third of the original 1720s French Fort Condé at the site, also known as Fort Carlota (under Spanish rule) and also Fort Charlotte (under British or American rule).

Forte Charlotte Mobile, AL

“Southern Markets Erected on Fort Charlotte’s Foundations, S. Royal St., Mobile, Ala.” ca. 1900 (Alabama Department of Archives and History)

Fort Charlotte was built by the French

Fort Charlotte was built in 1717 by the French as Fort Condé when Mobile was part of the French province of Louisiana (New France). By 1763, when the British took over following the French and Indian War, the fort was in ruins. While it was repaired at that time, by the time hostilities with Spain neared in 1779, it was again in disrepair. The garrison’s regulars were primarily from the 60th regiment and were augmented by Loyalists from Maryland and Pennsylvania, as well as local volunteers, in total about 300 men.

Join our Alabama Pioneers Patron Community!’

See how to Become an Alabama Pioneers Patron

When Spain entered the American Revolutionary War in 1779, Bernardo de Gálvez, the energetic governor of Spanish Louisiana, immediately began offensive operations. In September 1779 he gained complete control over the lower Mississippi River by capturing Fort Bute and then shortly thereafter obtaining the surrender of the remaining forces following the Battle of Baton Rouge. Following these successes, he began planning operations against Mobile and Pensacola, the remaining British presence in the province of West Florida.

A British (later American) fortified post, at Mobile, formerly called Fort Conde by the French. By the Treaty of Paris, February 10, 1763, when West Florida became a British possession, Major Robert Farmer was placed in command of the Mobile district. The old brick French Fort Conde’, built by Bienville in 1717 to replace the earlier Fort Louis, was immediately repaired and garrisoned. It was renamed Fort Charlotte, in compliment to the young queen of England.

Little interest was shown in Fort Charlotte for many years, owing perhaps to the bad health of the place. In March 1771, the fort underwent many repairs. However, in June of that year, Holdimand removed 12 12-pounders from Fort Charlotte to Pensacola, replacing them with small pieces.

Galvez made an attack upon Mobile

In 1780, Galvez, the governor of Spanish Louisiana, made an attack upon Mobile. The Fort was under the command of Elias Durnford, with a garrison of only 279 men besides the minister, commissary, surgeon’s mate, and ‘about 52 negro servants.

Gálvez assembled a mixed force of Spanish regulars and militia in New Orleans. While he had requested additional troops from Havana for operations against Mobile and Pensacola in 1779, his requests had been rejected. Before departing New Orleans, he dispatched one of his lieutenants to Havana to make one last request. On January 11, 1780, a fleet of twelve ships carrying 754 men set sail, reaching the mouth of the Mississippi on January 18.

They were joined on January 20 by the American ship West Florida, under the command of Captain William Pickles and with a crew of 58. On February 6, a hurricane scattered the fleet. Despite this, all ships arrived outside Mobile Bay by February 9. The fleet encountered significant problems getting into the bay. Several ships ran aground on sandbars, and at least one, the Volante, was wrecked as a result. Gálvez salvaged guns from the wreck and set them up on Mobile Point to guard the bay entrance.

On February 20, reinforcements arrived from Havana, bringing the force to about 1,200 men. By February 25, the Spanish had landed their army on the shores of the Dog River, about 10 miles (16 km) from Fort Charlotte. They were informed by a deserter that the fort was garrisoned by 300 men.

Ever since news of Gálvez’ successes had reached Mobile, Elias Durnford, commander of the Fort had been directing improvements to the fort’s defenses. with a garrison of only 279 men besides the minister, commissary, surgeon’s mate, and about 52 negro servants.

On March 1, Gálvez sent a letter to Durnford offering to accept his surrender, which was politely rejected. Gálvez began setting up gun batteries around the fort the next day. Durnford wrote to General John Campbell at Pensacola for reinforcements. On March 5 and 6, most of the Pensacola garrison left on a march toward Mobile. Due to delays crossing rivers, they could not arrive in time to assist the besieged.

Durnford torched the city of Mobile

In anticipation of the battle, Durnford torched the city of Mobile to prevent its houses and shops from being used as cover by the attacking army. It was a wasted gesture that caused enormous suffering for the inhabitants of the city. While the Spanish engaged in siege operations to move their guns nearer the fort, Gálvez and Durnford engaged in a courteous written dialogue. For example, Gálvez politely criticized Durnford for burning some houses to deny the cover they provided to the Spaniards.

Durnford responded by pointing out that the other side of the fort (away from most of the town) offered a better vantage point for attack. All the while, the Spanish continued to dig trenches and bombard the fort. On March 13, the walls of Fort Charlotte were breached, and Durnford capitulated the next day, surrendering his garrison.

Gálvez did not immediately move against Pensacola after his victory at Fort Charlotte, although he wanted to take advantage of the British disorganization caused by the attempt to support Mobile. However, since he knew that Pensacola was strongly defended, and armed with powerful cannons, he again requested large-scale naval support from Havana. He learned in April that additional reinforcements, including British Navy vessels, had arrived at Pensacola. Without reinforcements, he left a garrison in Mobile and left for Havana to raise the troops and equipment needed for an attack on Pensacola.

Gálvez did not actually launch his successful attack on Pensacola until 1781, and then only after the garrison at Mobile fended off a counterattack by the British in January 1781.

The first Spanish commandant at Mobile was Jose de Espeleta, followed by perhaps a dozen others. Among them were the well-known Folch Lonzas and Osorno. Perez was the last.

The fort was surrendered without bloodshed

Under an act of Congress in the spring of 1813, President James Madson directed Major-Gen. James Wilkinson to take Mobile. Commandant Perez was in no condition to resist and after negotiations, surrendered the Fort, on April 15, 1813, without bloodshed.

During French, British, and Spanish rule, Fort Charlotte had been the important center of Mobile life, but now that Florida had become a part of the United States, and Mobile was growing up around the Fort, there was a feeling that it should be torn down and the ground be converted into city lots.

Although Major-General Bernard on December 23, 1817, made a report to the U. S. chief engineer that of all the forts in Louisiana, Fort Charlotte was the only one well built, and recommended it be retained, the sale of the old Fort was authorized by act of Congress, April 20, 1818. This act was not carried into effect, however, and it remained garrisoned until 1820. The sale actually took place in October 1820, much of the property going to a syndicate, calling itself the Mobile Lot Company.

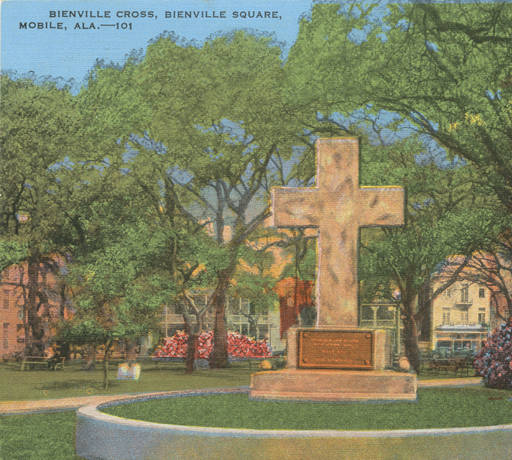

Mobile was originally founded, by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, in 1702 as Fort Louis de la Mobile at 27 Mile Bluff upriver (27 miles [43 km] from the mouth). After the Mobile River flooded and damaged the fort, Mobile was relocated in 1711 to the current site. A temporary wooden stockade fort was constructed, also named Fort Louis after the old fort upriver. In 1723, construction of a new brick fort with a stone foundation began renamed later as Fort Condé in honor of King Louis XIV’s brother.

Bienville Cross in Mobile

Fort Condé guarded Mobile and its citizens for almost 100 years, from 1723 to 1820. The fort had been built by the French to defend against a British or Spanish attack on the strategic location of Mobile and its Bay as a port to the Gulf of Mexico, on the easternmost part of the French Louisiana colony. The strategic importance of Mobile and Fort Condé was significant: the fort protected access into the strategic region between the Mississippi River and the Atlantic colonies along the Alabama River and Tombigbee River.

Fort Condé and its surrounding buildings covered about 11 acres (45,000 m2) of land. It was constructed of local brick and stone, with earthen dirt walls, plus cedar wood. A crew of 20 black slaves and 5 white workmen performed original work on the fort. If the fort had been reconstructed full-size, it would cover large sections of Royal Street, Government Boulevard, Church, St. Emanuel, and Theatre Streets in downtown Mobile

Support Alabama Pioneers with your Donation, any amount helps!

During 1763 to 1780, England was in possession of the region, and Fort Condé was renamed Fort Charlotte in honor of King George III’s wife.From 1780 to 1813, Spain ruled the region, and the fort was renamed Fort Carlota. In 1813, Mobile was occupied by United States troops, and the fort was renamed again as Fort Charlotte

In 1820, the U.S. Congress authorized sale and removal of the fort because it was no longer needed for defense. Later, city funds paid for the demolition to allow new streets built eastward towards the river and southward. By late 1823, most of the above-ground traces of Mobile’s fort were gone, leaving only underground structures.

SOURCES

- Pickett, Alabama (Owen’s ed., 1900), pp. 321, 516;

- Hamilton, Mobile of the five flags (1913), pp. 130, 190, 211;

- Hamilton, Colonial Mobile (1910), pp. 217, 252, 255, 266, 309, 412, 478.

See a list of all books by Donna R Causey at amazon.com/author/donnarcausey

Read this story and more in ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Exploration: Lost & Forgotten Stories (Volume 1), a collection of lost and forgotten stories about the people who discovered and initially settled in Alabama.

Some other stories include:

- The true story of the first Mardi Gras in America and where it took place

- The Mississippi Bubble Burst – how it affected the settlers

- Did you know that many people devoted to the Crown settled in Alabama –

- Sophia McGillivray- what she did when she was nine months pregnant

- Alabama had its first Interstate in the early days of settlement

[…] one story high. At the south end of the town is a beautiful fort, built by the French and called Fort Charlotte. The town is about thirty miles north of the Gulph of Mexico, at the head of what is called Mobile […]

Really now 🙂

Why am

I learning this 41 years late?

It’s amazing how much was left out of our Alabama history textbooks.

At least Alabama teaches history I was so disappointed in 1978 when I moved to Florida to discover there was no Florida history course in school.

Because we didn’t have fb post to learn from when we were in school. Lol

I actually was punished for being a smart ass in 4th grade history class. I read everything the school library had on history in 3rd grade and would correct my 4th grade teacher. She did not appreciate that.

Wow that’s cool

No I had no ideal

Where can we find the names of the patriots who were stationed there?

Try checking with the Mobile Library. They have wonderful historical records and should be able to guide you to a source. http://www.mobilepubliclibrary.org/

Donna

A friend recently asked me to do a little genealogy on his family. I discovered that one of his ancestors came with Bienville to settle Mobile and later moved on to settle New Orleans. He was a brick maker and made bricks for the fort and building of Mobile and New Orleans (where he was given a house that is now a restaurant on Jackson Square). His wife was on the bride ship from France that first stopped at Dauphine Island before moving up the bay to Mobile. I was confused about the exact location of everything, and this article has helped me mentally place where all these events took place in Mobile. He will be visiting in September, and I intend to take him to these places. Thanks so much.

Glad to be of help! I hope you have a nice visit.

Donna

I enjoyed the old forts in Mobile, and Fort Morgan!

A family member’s name is on the Revolutionary War Memorial located in Linn Park in Downtown Birmingham, AL. His name was Michael McCarthy.

Thanks for the story. And no I did not know this but the next time I go to gulf shores I will be going to the fort.,and thanks for the awesome story. .

I’ve been here several times, we stayed at the campground 1/4 mile from the old fort. Well worth seeing.

Yes.

i did 🙂

Amy, you should tell Haley about this.

Love Alabama Pioneers. I was really surprised to learn that my 4th great grandfather said he participated in the Florida expedition during his service. He was S. C. Militia and recounted this in his Revolutionary War pension application.

The Weavers, Byrds, and Rivers owned a portion of Mobile until it was “SOLD in good hand writing” despite the fact that the families were well known not to be able to write at the time due to lack of any schools or very little.

The Choctaws were denied education for some time in Mobile and Washington Counties.

The public land records will vouch for the titles changing hands – particularly in the Texas street area but others…

Essentially, those who wrote those deeds and other agreements against the Choctaw Indians of Alabama violated the Non-Intercourse Act – making any and all such titles null and void in any Court of Law – 25 U.S.C. 177 (1834, 2006).

Zenon Orso was one of the people who surrendered the Pensacola Mound to Galvez and his lieutenant named Geronimo in 1781.

The Chastang and Pensacola Indians who were locals to the area assisted Galvez per Galvez’s detailed notes on the matter.

The Surrender on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroads by Richard Taylor to General Canby happened 14 miles north of Mobile per the Newspaper of the day…

Note: Not the Mobile and Ohio since it was the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad…

Funny how so many places in Alabama were named the same as the Eastern Coast where we were all taught the American Revolution transpired…

Look it up and be amazed…

Maybe the Revolution happened on the Gulf Coast after all…