During the 1930s, in the Great Depression era, many writers were employed to interview people and write stories about life in the United States. The program was named the U.S. Work Projects Administration, Federal Writers’ Project and it gave employment to historians, teachers, writers, librarians, and other white-collar workers.

Transcribed and unedited (with misspelled, capitals and grammatical errors) written by WPA (Works Projects Administration) writer Annie L. Bowman, Escambia County, Alabama, Feb. 3, 1939

The Hines Family

Atmore, Alabama

Teachers in Escambia County, Alabama

written by WPA author

Annie L. Bowman

February 3, 1939

Mary Hines is the mother of nine children, four of whom are dead. Leona, the oldest, is married and lives in Dothan, where she now teaches. Her other four daughters are also teaching. Elona, Myrtice and Pauline teach nearby and stay at home while Dorothy teaches in Columbia, Alabama. The youngest child, John Wesley is still in high school.

Lived somewhat better than average colored family

Since the girls are professionally employed, Mary’s family lives somewhat better than the average colored family. Each of the girls makes $30 a month and Mary makes some on the side with her washing. They are now trying to redeem their home which they lost during the depression. To do this they will have to pay $5 a month to the government for the next seven years. This much better than paying rent.

Down the highway through the Atmore Negro quarters, this house, somewhat better looking than the other makeshift structures which the Negroes call their homes, is approached.

A gate gives access to a neatly trimmed and freshly swept front yard. An old half-blind Negro was in the back yard cutting wood when we arrived.

To the question, “Is Mary at home?” came the reply:

“Yes Ma’am, she were in there an hour ago,” he answered, as he shuffled into the house to find her.

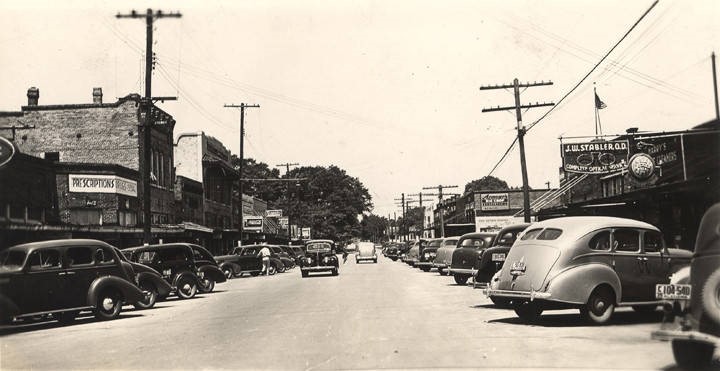

Business section on North Main Street in Atmore, Alabama 1930s (Alabama Department of Archives and History)

Inviting appearance

Mary came to the door with an invitation into the parlor. One who is used to going into colored folks’ homes is sure to be amazed at the inviting appearance of this one. The parlor has a living room suite, piano, and rug on the floor. The fireplace has an old iron pot on the coals.

“Yes, I’m trying to save fuel by cookin’ my dinnah on the fire,” she explained. The room has two beds, covered with neat cotton counterpanes, a sewing machine and three chairs, one a rocker.

She has been sewing on quilts and she proudly displayed three that she has recently pieced.

The girls’ room had a bed, table, wardrobe, dresser and two rocking chairs. In the guest room is a neat bed-room suite, and a wardrobe, washstand, a rug and two chairs. John Wesley’s room also serves as the pantry. Mary says that she keeps her canned fruit there; and she displayed the kitchen and dining-room, which are common in appearance but clean.

She said, “The girls warned me this morning that if they left without cleaning up the house, I would neglect it and company would surely come and now, sure enough, you’re here.”

Husband was half-blind

Just then the door opened and her half-blind husband walked in. He appeared to be about seventy-five years old. He told me that he could see a little since he was operated on. He then proudly displayed that he could work his own garden, and he then pointed out the window to prove it.

“I couldn’t give satisfaction by hiring myself out to anyone else,” he added, “but I can pick cotton a little. The bolls are so big and white that I can see many of them and feel the rest. So you see I can do a good day’s work yet,” he explained.

“Today, our new governor goes in office. I kept telling the old lady that I wish we had a radio so we could hear his inaugural address. Well, he has a load on his shoulders and I guess he is a lot like school teachers. They walk into the room the first morning with high hopes, but before it’s over, we are doing the best we can.”

Location of Escambia County, Alabama

The government made two classes of the American people

He went on about the Federal government, “I don’t believe there’s going to be any tenant farmers anymore, since the government has fixed it so the tenant farmer can get half the subsidy. The landlords will just hire help and you can work it or let it alone which means that most of them will work at any price to keep from sharing. The government has just made two classes of the American people. The lower class has turned to beggars; the higher class has turned to grafters. That comes from putting so much money in their control.

He then asked if I had read about the tenant farmers in Arkansas. Then he left the room to go out in the garden to work. I wondered where he got his information until I notice the Montgomery Advertiser and the Mobile Register lying on the sewing machine.

Born in Monroe County

Mary was born in Monroe County, one of seven children. Her father, David McCants was a slave before the war. He didn’t remember much about slavery, however, for his mother and father were freed when he was a child. They kept the name of McCants, their master.

When Mary was four years old, her father and his family moved to Wilcox County near Pineapple and lived there as tenant farmers until she was grown. Before going there he had been a tenant farmer for David Watts.

In 1911, the family moved to Escambia County where farming conditions were better, and the father worked for John Maxwell and Mr. Wagner until he died.

Mary again took up the conversation. “I stayed with my ma longer than any of her seven children. All the others married and left home and I decided to become a teacher. I begged my ma and pa to let me go to school. They finally consented to let me go to the Colored Industrial Seminary at Snow Hill. I worked there in the laundry for my board.”

Map of Alabama with counties

Them was happy days

She sat for a while, gazing out the window.

“Them was happy days. I just loved it all. I finished the eleventh grade and took state examination. I then taught school for three years. Then I married at the age of twenty-five. I had done give up hopes of ever marrying by then, and sometimes I wish I never had.”

She confessed that she had a very desperate love affair when she was very young. “Lord how I loved that man,” she recalled. “He was no account so ma, she just broke it up. I grieved so hard after he married that the neighbors said it was a sin to covet another woman’s husband. I went to church one day and the preacher said it was a shame and disgrace to grieve over spilt milk. I’ve seen him several times since and it seems now that I am just meeting a dear old friend.”

“I was teaching at Wallace when Dock Hines’ wife died. She was giving birth to a baby girl. It wasn’t long before he came a courtin’. I decided that I was getting to be an old maid. If I ever married I had better take him. I never loved my old man but I respected him. After I bore him nine children, I couldn’t give him up. He got sick and blind and I’m certain that it’s my duty to keep up with him.”

“After we were married, I went with him to Camden to live. He was teaching there. Dock taught school for twenty-five years. I as ailing that winter and was homesick for pa and ma. When school closed, we moved back to Escambia County.”

Worked in sawmill

“Dock kept teaching and pea-patching until three of my children were born. He only made $27.00 per month and I can tell you them was hard times. He finally quit teaching and went to work at a sawmill for Mr. Harry Patterson. Pay was better there and he worked for fourteen years at this mill. In 1926 it closed down.”

“By that time I had raised most of my family. Four of them had died, the screech-owl screeched in the Chinaberry tree by the door. Them was bad signs and I knowed right away that something bad would happen.”

At this point Mary paused with a sorrowful sigh as these sad memories came back to her. She got up and walked about the floor before she continued her story.

After her children’s death, her husband’s eyes began to fail. He would not tell any of the family about it, but they could tell by his feeling and fumbling around. This incapacitated him for holding a job, and he has not worked regularly since.

No money for an operation

These were hard times for Mary and her family. Old Dock lost his sight entirely. According to the doctors, a cataract had covered his eyes and sight was impossible without an operation. There was no money in this poor family for one.

Mary continued, “To keep from starving I gathered my four girls and John Wesley and went tot the field to hoe. I put the baby in a corner of the fence in a big cotton basket, and there we hoed, picked cotton and strawberries from morning until dark. We kept together some way, sometimes I wonder how.”

Mary was interrupted by John Wesley coming home from school. He is a big overgrown boy who will finish high school this year if he passes his grades. Mary ordered him out of the room to go help his father get the wood cut but as I looked out of the window, I could see him going to the playground with a ball under his arm. Mary saw him at the same time and declared, “That is the most trifling boy I have ever seen. I’ll get him yet for this. I don’t know what’s goin’ to become of him.”

Like many of her race and sex it is plain that she doesn’t put any dependence in any boy or man. It is further shown when she makes a remark about Dock. “My ol’ man is not brutal – jus’ shiftless, but I guess it is because of his health.”

Escambia River

Always want them to go to Methodist Church

Mary spoke of the possibilities of the future. “Now, if I can keep my girls at home for seven years longer, we can pay off the mortgage; but one of them has a suitor – a teacher at Freemanville who has been paying her court. If the other two has ever had a beau, I don’t know it. I reckon though it would be better for them to marry before one of them should disgrace herself. But if I even so much as mention such things to them, it makes them mad. They always claim that they are old enough to take care of themselves. But I don’t know and nobody else knows what a girl might do. After all my raising them right; I always made them go to the Methodist Church with me and tried to bring them up in the straight and narrow way; but I didn’t spare the rod either. But if some wolf in sheep’s clothing should ruin one of my daughters by big promises and honeyed words, I wouldn’t leave it up to the Lord. No ma’am, not me.”

She is one of the strictest members of the Methodist Church; and she can shout louder than most of them when the spirit gets her, she says.

Harry Patterson paid for an operation

Mary said of her husband, “We were speaking about Dock’s eyes. He was a terrible care, a main ailing and me with a living to make, but one cold day I was sitting in my room – brooding, praying and wondering what we were going to do. We had no wood and nothing else much. When I heard a knock I went and opened the door. You could have knocked me down with a feather. Mr. Harry Patterson, a man Dock had worked for fourteen years, stood in the door. The spirit rose but I said to myself, ‘Down spirit, wait ’till Marse Patterson goes home. Then you can do all the shouting you want.’ He had heard of our plight and had come to see about taking the old man to a hospital for an operation. I have never been as happy since I was in Snow Hill in the seminary.”

Dock Hines was carried to the hospital and the cataract was removed, so that he can now see some out of that eye but a cataract has covered the other one.

The girls came in from school and greeted us courteously. They were dressed alike in plaid skirts and red topper coats. Their mother’s training showed in their pleasant manners and self-possession. Myrtice had a headache; as she lay down on the bed. Elona went to make a fire in the stove and fix supper. That was breakfast and supper when they got home from school. Myrtice, regardless of her headache, was in a talkative mood. She began to tell about incidents that had happened that day at school, and was telling me all about their school life.

Borrowed money to send girls to school

“All the time that we were working in the field, Elona and I were planning to go to school. We didn’t see how we could for we had no money, but we didn’t give up hope. After we finished high school, we wrote to the Alabama State Teachers’ College in Montgomery, the school for colored. The principal got a place for us to work in Cloverdale, with some of the rich white people and go to school. We borrowed some money from Mr. Jones, a banker, and promised to pay him in the summer by working on his farm. This we did. He was glad to help us. It didn’t take much, just train fare and a few clothes. We worked hard at the white folks’ house and went to school during the day. We stayed all that first winter.”

“The next year we couldn’t be spared at home. Mama couldn’t take the load by herself. Dorothy and John Wesley were still in high school at home. The next year Elona went back for four months, and the summer following, she went for three months. That winter we both stayed in school. Dorothy was large enough to work and help at home and Papa was assigned to teach an adult school.”

Daughters are teaching

“Elona was able to teach the next winter but Papa lost his job after she began teaching. We have both been teaching for three years now and Dorothy, with the help of Federal aid, spent three years in Huntsville school. She is now teaching in Columbia, Alabama. We miss her very much but we are making a living. When school closes, we work in the field.”

Elona came in the room to announce the early supper. They were hungry because they hadn’t eaten since breakfast. They were planning to practice their pupils in a play that the school was giving for the benefit of the library.

They say that their only recreation is school entertainments and church and Sunday School activities, but they make the most of this for Mary would never let them go to parties and now they never get invited.

As I left the house I wondered if education with the right kind of environment isn’t the greatest boom for the young of any race.

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS – Volume I – IV: Four Volumes in One (Volume 1-4)

BUY ONE GET ONE FREE! The first four Alabama Footprints books have been combined into one book,

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Exploration

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Settlement

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Pioneers

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Confrontation

From the time of the discovery of America restless, resolute, brave, and adventurous men and women crossed oceans and the wilderness in pursuit of their destiny. Many traveled to what would become the State of Alabama. They followed the Native American trails and their entrance into this area eventually pushed out the Native Americans. Over the years, many of their stories have been lost and/or forgotten. This book (four-books-in-one) reveals the stories published in volumes I-IV of the Alabama Footprints series.