“As long as you speak my name, I shall live forever

JOIN US FOR FREE

CANCEL ANYTIME

Become an Alabama Pioneers Patron

(Excerpt from ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS: Banished Volume 8)

On the road leading from St. Stephens in Washington County, Alabama, lived the renowned Choctaw Chief Pushmataha. In 1812, a mound, Nunih Waiyah1 stood nearby. It is said that the mound was erected by the earliest Choctaws in commemoration of their migration from a country far to the west to their homes east of the Mississippi River where they first met the Europeans. The Choctaws lived around their honored memory of the past for many successive generations, but this all changed in 1830.

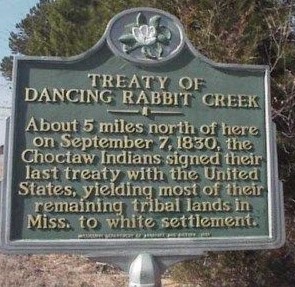

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek with the Choctaws was the first removal treaty carried into effect under the Indian Removal Act on September 27, 1830. The treaty ceded about 11 million acres of the Choctaw Nation in exchange for around 15 million acres in the Indian Territory of present-day Oklahoma. Article Fourteen of the treaty allowed some Choctaw to remain in the state of Mississippi if they wanted to become a citizen:

ART. XIV. Each Choctaw head of a family being desirous to remain and become a citizen of the States, shall be permitted to do so, by signifying his intention to the Agent within six months from the ratification of this Treaty, and he or she shall thereupon be entitled to a reservation of one section of six hundred and forty acres of land, to be bounded by sectional lines of survey; in like manner shall be entitled to one half that quantity for each unmarried child which is living with him over ten years of age; and a quarter section to such child as may be under 10 years of age, to adjoin the location of the parent. If they reside upon said lands intending to become citizens of the States for five years after the ratification of this Treaty, in that case a grant in fee simple shall issue; said reservation shall include the present improvement of the head of the family, or a portion of it. Persons who claim under this article shall not lose the privilege of a Choctaw citizen, but if they ever remove, they are not to be entitled to any portion of the Choctaw annuity.

The United States Government appointed John H. Eaton, the Secretary of War, and General John Coffee, of Lauderdale County, Alabama as Commissioners to treat with the Choctaws for the sale and cession of their lands. Located in Winston or Noxubee County, Mississippi, Dancing Rabbit Creek was agreed upon as the place to treat by the Indians and the two Commissioners.

The following transcription is an excerpt from an article by Anthony Winston Dillard of Gainesville, Alabama that was published in Transactions of the Alabama Historical Society, Volume 3, 1899. It reveals many of the events and the conversations that took place at this historic meeting and also illustrates the tension among all those who participated.

The government entered into a contract with Colonel Gaines to have on the ground selected for the conference, a supply of provisions sufficient to subsist 3,000 persons for a week, and he had collected this supply of provisions at considerable expense and trouble to himself. The Indians used paths, and had no roads hence Colonel Gaines was compelled to transport the supply of flour and corn meal on Indian ponies to the place of meeting.

The United States Commissioners arrived at the meeting place agreed upon and found a large number of Indians already assembled.

The conference was opened by the commissioners. They stated that the purpose and object of this conference was to make and enter into a treaty with the Choctaws for the sale and cession of all their lands situated in Alabama and Mississippi to the United States, and for the removal of the Choctaws to lands west of the Mississippi, such lands to be selected by the warriors chosen by the Choctaws.

Colonel Gaines said this proposition acted as a bomb thrown among the Choctaws. It filled them with surprise, astonishment, excitement, grief, and resentment. Not a single Choctaw favored the sale and cession of the lands of the tribe. It had not a solitary advocate among them.

John Pitchlyn, who spoke both the English and the Choctaw languages fluently, was hired by the Federal government to act as interpreter for the occasion. 2

The Indians, according to Colonel Gaines, drew up and signed, in their rude fashion, a “Round Robin,” denouncing and threatening death to any chief who should sign a treaty for the sale and cession of the lands of the tribe and for the removal of the tribe across the Mississippi River. This indignant protest was duly presented to the leading chiefs.

The Choctaws constituted a confederacy. The territory of the tribe was divided into three divisions, and each of the divisions was ruled by a chief, chosen by the warriors in his division. These chiefs had only the care and regulation of local affairs in the territory assigned to them, by metes and bounds.

The three chiefs of the Choctaw Confederacy, at the date of the Dancing Rabbit Treaty, were Greenwood Leflore, in the Western Division, who lived near the present site of Yazoo City. He was the son of a French trader and merchant who had settled among the Choctaws and married a Choctaw woman. This chief refused to remove west of the Mississippi and resigned his chieftainship. He was, for several years, a State Senator in Mississippi, and Gov. John J. Pettus, who was also a State Senator, informed me that on a bill to regulate the sale of liquor coming up for discussion, Leflore made one of the most pathetic, impassioned and eloquent speeches he ever heard in opposition to the sale of “fire water.”3 He said the whites had introduced the destroying angel—”fire-water”—among his race, and it had blighted, withered, and ruined his race, the Indians. And the white man, who prided himself on his civilization, intelligence, and piety, had often made the Indians drunk with “fire water,” and while they were in that condition, gone through the farce of buying their lands at the most trifling price.

Mushulatubbee was the chief of the Northeast Division. The father of the writer of this article (Anthony Winston Dillard) purchased from Mushulatabbee the tract of land assigned him by the Dancing Rabbit treaty and resided there from Dec. 1, 1832, to Dec. 1, 1834.4

The chief of the Southeastern Division was named Nittakechi, who resided near the site of Daleville, Lauderdale County, Mississippi. He was third in succession from Pushmataha and was the oldest and most influential chief. He was gifted with great decision of character and doggedness of purpose, traits which never fail to add to the weight and influence of men irrespective of race.

Col. Gaines said all the Indian chiefs spoke with energy and impassioned eloquence against the sale and cession of their hunting grounds. They dwelt on the fact that the Choctaws had always lived on terms of friendship with the white man from the time of his first landing on their shores, and had never been engaged in war with the French, the Spanish, the English, or the Americans.

When Bill Weatherford was making war on the whites in Alabama and was about to destroy them, the Choctaws had raised a band of 300 warriors, headed by Pushmataha, and, joining the American army, had fought against the Creeks. This proof of friendship on the part of the Choctaws for the Americans had been forgotten by the whites, who now proposed to force the Choctaws to sell and leave the hunting grounds of their fathers.

A sub-chief, called Little Leader,”6 surpassed all the Indians who spoke on this occasion in energy of expression and fiery eloquence. He declared he would neither sell nor leave the lands and homes of his fathers, and that he would go away and gather his warriors for the protection of the homes of his people.

The white man had neither justice nor gratitude, but wanted to strip the Red man of all his lands and move him across the Mississippi to strange hunting grounds, where water and wood were both scarce. The Choctaws had already sold all their lands on the east side of the Tombecbee to the white man, but now he wanted to get possession of all their other lands and to move them to a strange country, unknown to their fathers. And even should the Choctaws consent to sell the hunting grounds of their fathers and to go to strange hunting grounds, the time would come when the white man would want to get hold of their new hunting grounds, and to move the Choctaws once more.

Our fathers and our children are buried in our present hunting grounds, and the graves of their fathers are dear to the hearts of the Choctaws; we love our hunting ground more than the white man loves his country, and we do not want to be driven away from them. Any chief who may sign a treaty selling our lands is a traitor and should suffer death. I go home to prepare to fight for our homes and the graves of our fathers.

At this stage of the proceedings, John H. Eaton rose and said, with brutal bluntness, that the Choctaws had no choice in the matter, but were bound to sell their lands and remove to the other side of the Mississippi River.

If they refused to enter into a treaty to this tenor and effect, the President, in twenty days, would march an army into their country—build forts in all parts of their hunting grounds, extend the authority and laws of the United States over the Choctaw territory, and appoint United States judges to try the, Choctaws by the laws of the United States.

Sheriffs and constables would also be appointed and sent among them. The soldiers would support and defend the constables, sheriffs and judges that would be sent among the Choctaws to maintain and enforce the laws of the United States.

Should the Choctaws go to war with the United States it would be just as foolish as it would be for a baby to expect to overcome a giant. The result of the Choctaws making war on the United States would be the ruin of the tribe—their lands would be seized on as the property of an enemy and the Choctaws would be forcibly removed across the Mississippi.

General Coffee magnanimously rose to his feet, and declared his strong disapprobation of the course adopted by his brother commissioner in the matter, and avowed he would have no hand in that sort of proceeding.

The Indians were indignant and resentful, and left the ground and started for their several homes in large numbers.

Mr. Eaton prevailed on the principal chiefs and a few inferior chiefs to remain and talk the matter over with him, and they complied with his request.

After all the other Indians had dispersed and started for their homes, Eaton held a private or secret conference with the chiefs who, at his request, had remained, and by some means prevailed on them to sign the Dancing Rabbit Creek treaty.

No doubt he accomplished this result by threats and intimidation, mingled with the promise of sugar coating the obnoxious treaty by embracing in it a clause allowing the chiefs a specified number of acres of land, proportioned to their rank; and the private male Indians, who were heads of families a specified number of acres, all the lands to be selected by each individual Indian.

The Indians were in resentful and indignant mood and ready to take fire at any chance spark falling among them. Little Leader was openly getting up a band of Indians to resist the enforcement of the obnoxious treaty brought about by questionable and reprehensible means.7

The commissioners appealed to Col. Gaines to act as a pacificator (sic) on this occasion. He was appointed to conduct and superintend the removal of the Indians to their new territory. He was also appointed to go with a delegation of Choctaws across the Mississippi, in order to select the new settlement of the Choctaw tribe.

Col. Gaines enjoyed the confidence and respect of all the Choctaws, most of whom he knew personally. He went among them, and succeeded in persuading them to abide by the treaty, telling them, he had been appointed to go with a body of Choctaws across the Mississippi to select and locate the new hunting grounds of the tribe, and that their new territory would be as good, if not better, than their old hunting grounds.

He also told them he had been appointed by the commissioners to conduct and superintend the removal of the Choctaws across the Mississippi to their new hunting grounds, and that the government had agreed to furnish wagons enough to haul the aged and infirm and the women and children. Col. Gaines soon extinguished the war spirit among the Indians, and reconciled their minds to the removal.

George W. Harkins,8 the nephew of Choctaw Chief George W. Harkins, wrote the following emotional letter to the American people before the removals began.

We go forth sorrowful, knowing that wrong has been done. Will you extend to us your sympathizing regards until all traces of disagreeable oppositions are obliterated, and we again shall have confidence in the professions of our white brethren? Here is the land of our progenitors, and here are their bones; they left them as a sacred deposit, and we have been compelled to venerate its trust; it dear to us, yet we cannot stay, my people is dear to me, with them I must go. Could I stay and forget them and leave them to struggle alone, unaided, unfriended, and forgotten, by our great father? I should then be unworthy the name of a Choctaw, and be a disgrace to my blood. I must go with them; my destiny is cast among the Choctaw people. If they suffer, so will I; if they prosper, then will I rejoice. Let me again ask you to regard us with feelings of kindness.

Col. Gaines reported the following to the writer (Anthony Winston Dillard) about the events that followed the signing of the Dancing Rabbit Creek Treaty.

Little Leader found himself without followers, but he scornfully refused to remove and lived and died in Mississippi. Col. Gaines went with a body of Choctaws and selected the territory now occupied west of the Mississippi by the Choctaw tribe.9

When the first Choctaw emigration across the Mississippi took place they offered to elect Mr. Gaines head chief of their tribe if he would consent to go permanently with them to their new hunting grounds. He declined on account of his wife and children, whom he was unwilling to banish from civilized society and subject them to a residence among the Indians.

He was appointed to conduct and superintend this removal of the first body of Choctaws to their new hunting grounds, but he informed me (Anthony Winston Dillard) that the government had so shamefully broken its promises in reference to providing wagons to transport old and decrepit Indians and the women and children, and that he had witnessed so much hardship and suffering among the Indians whom he had removed that he resigned his position of director of the removal of the Choctaws.

Gaines stated that they contracted with him to provide provisions sufficient to subsist 2,500 persons for a week at the treaty site on Dancing Rabbit Creek, and that he had transported an ample supply of provisions to the selected spot, but as the Indians left on the evening of the first day of the conference, and returned to their homes, the United States government had paid him for but one day’s provisions, and left the other six days’ provisions on his hands, thereby entailing on him a considerable loss of money.

Maj. John C. Whitsett then living in Greene County, Ala., was present at the Dancing Rabbit treaty, and saw and heard all that was either said, or done, on that occasion.

1Nanih Waiyah is an ancient earthwork mound in southern Winston County, Mississippi. Some Choctaw believe that Nanih Waiya is the “Mother Mound” (Inholitopa iski) where the first Choctaw was created.

2’His wives were: (i) Rhoda Folsom, and (2) Sophia Folsom, both of whom were of mixed blood. One of his sons was Major Peter Pitchlyn, prominent in the Choctaw Nation. Major John Pitchlyn died in 1835, aged about 70 years, and is buried on the Tombigbee river, not far from Waverly.

3His father was Louis LeFleur (improperly called Leflore), a “small man, a Canadian, speaking a singular patois of provincial French and Choctaw.” For a sketch of him see Claiborne’s Mississippi, p. 116. For sketches of Greenwood Leflore see, Ibid p. 515, with portrait; and Lowry and McArdle’s History of Mississippi (1891), pp. 450-2. He lived in Carroll Co., Miss., which he represented in the State Senate, 1840-43. A county of that State has been named for him. There are descendants both in Miss. and in the Choctaw Nation. Ben Leflore, brother of Greenwood, married a daughter of Pierre Juzan. She was a grand niece of Pushmataha. See also W. T. Lewis’ Centennial History of Winston County, Miss.; H. B. Cushman’s MS. History of the Choctaws; and Senate Report, No. 314, April 29, 1874, on the petition of John D. Leflore and James C. Harris, executors of the last will of Greenwood Leflore, 43rd Cong. 1st Sess.

4He had two homes in Mississippi, one in Noxubee Co., about five miles northeast of Brooksville, the other at the present village of Mashulaville, named for him. He died in 1849 in San Bois Co., Choctaw Nation. Meager references are found in Claiborne, p. 508; Gaines’ Reminiscences; and Lewis’ Winston County. For etymology of name, see Trans. Ala. Hist. Society, 1897-98, vol. ii, p. 109; and as to how he received the name see Miss. School Report, 1893-95, p. 544.

5Col. Gaines had a high admiration for this chief, as appears from a sketch of his character furnished Mr. Lewis, and used by him in his History of Winston Co. He died about 1836 or 1837 on the Red River in the Choctaw Nation.

6This was Hopaii Iskitini, who lived two miles in a southern direction from Narketa, Kemper Co., Miss., on the south side of Sukanatcha, and a quarter of a mile away. He died about 1847, and is buried at his home place.

7The picture here presented of the excited conditions of the Indian mind is probably not overdrawn. Mr. Lewis of Winston County says: “After the treaty, the disaffected Indians made an attempt to get drunk for the purpose of mobbing Eaton and Coffee, who made the treaty with them; and they only desisted from their design upon Gaines’ promising that he would accompany the Choctaw Commissioners [Delegation] to examine the country west of Arkansas.”

8George W. Harkins (1810–1890) was an attorney and prominent chief of the Choctaw tribe during Indian removal. Harkins was born into a high-status Choctaw clan through his mother, Louisa “Lusony” LeFlore. His father was John Harkins, a European American.

9Being appointed to conduct the Choctaw exploring delegation composed of 12 or 14 noted Choctaws, among these Mingo Nettakechi, the whole party well mounted, proceeded at once in the early fall, from the Coosha towns, in the northern part of Lauderdale Co., Miss., in the vicinity of old Daleville, across the county to the residence of Col. LeFlore on the Yazoo – thence across the Miss. River to Arkansas Post, Little Rock, and Fort Smith to the new country. Col. Arbuckle at Fort Smith was instructed to furnish them with supplies for this exploration. A thorough exploration was made. Upon the return of the del.. in February, they made such a favorable report that a great many Choctaws became reconciled to the emigration. No official report of this expedition has been found. Accounts of it rest on the authority of statements furnished by Mr. A. J. Picktett and Mr. W. T. Lewis, who has some account of it in his History of Winston County.

READ MORE ABOUT THE TREATY FROM EYEWITNESSES IN THE BOOK

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 marks a dark time in American history regarding the new country’s relationship with the Native American population. The Act called for the “voluntary or forcible removal of all Indians” residing in the eastern United States to the west of the Mississippi River. Between 1831 and 1837, approximately 46,000 Native Americans were forced to leave their homes in southeastern states.

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS: Banished reveals true stories, documents, and news articles from this sad time in Alabama’s history. Some stories include:

- Choctaw & Treaty Of Dancing Rabbit Creek

- Private Contracts For Removal

- Stockades In Alabama

- The Long Trail West

- Reverend Daniel S. Burtrick’s 1838 Journal

- An Observer Writes His Memories