This story is an excerpt from the book ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Settlement: Lost & Forgotten Stories (Volume 2)

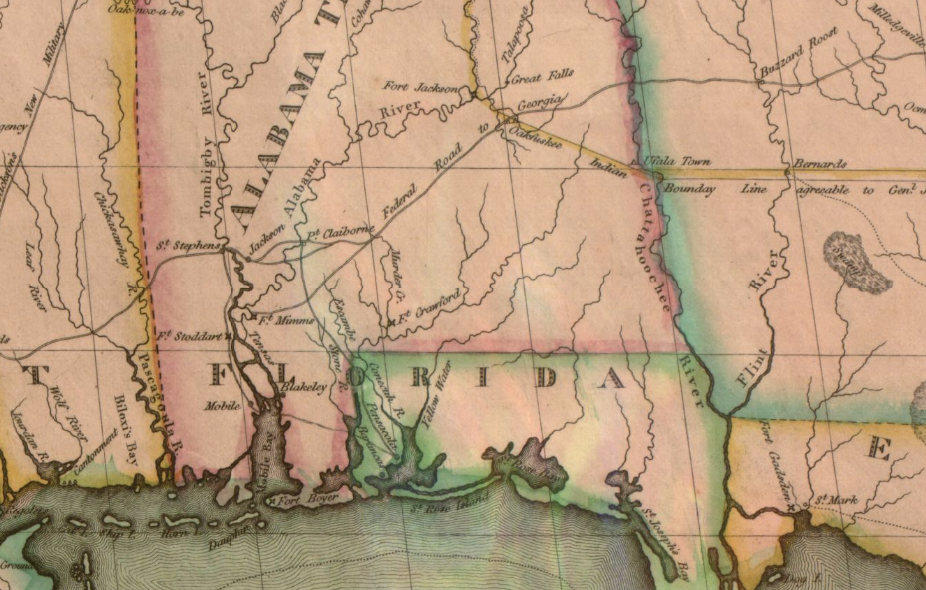

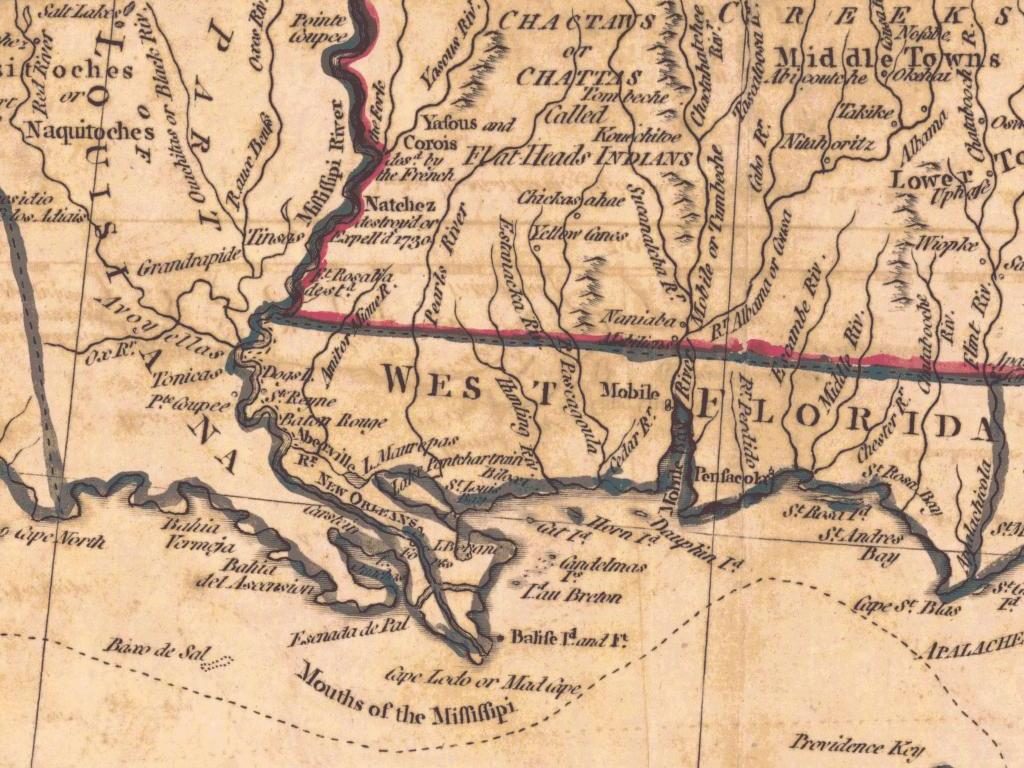

French trade from Mobile was principally by the river, but there was a land route to Fort Toulouse, which doubtless joined the one from Pensacola, running through thick forests south of the Alabama to the same place.

The traders generally went in companies of fifteen to twenty men, with perhaps seventy to eighty pack and other horses. The horses were permitted to graze at night and the start in the morning was after the sun was high. The loaded animals fell into single file and were urged on with whip and whoop at a lively pace.

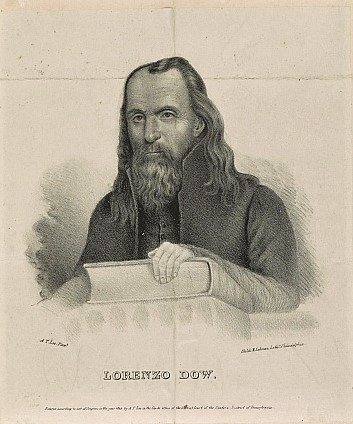

Lorenzo Dow (Library of Congress)

An instance of the difference between traveling before and after the Federal Road was cut may be found in the life of the eccentric but earnest Methodist preacher, Lorenzo Dow.

In 1803 he was in Georgia and set out for Tombigbee, by way of the agency of Hawkins, who “treated them cool.” In thirteen and a half days after leaving the Georgia settlements, they reached the first house in the Tensaw district.

His only notice of the “road or rather Indian path” was that they lost it once and then it took a good woodsman to find it again. He preached at Tensaw on a Sunday and kept also a string of appointments across the swamp and the rivers. This was at a thick settlement, which must have been about McIntosh Bluff, and a scattered one above, seventy miles long. It then took him six and a half days to reach the Natchez settlement.

1823 Map of south Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, & West Florida (Library of Congress)

At the end of December 1804, he returned, but the only road he mentioned is the trading road from the Chickasaws to Mobile, near Dinsmore’s agency and Fort St. Stephen. At St. Stephens he found but one family. He seems to have tarried six days in the Tensaw settlement, holding meetings, and in early January traveled on to Georgia.

Old Tavern in Limestone County, Alabama (W. N. Manning photographer – Library of Congress)

In the Creek nation, there were so many by-paths as to make it difficult to find their way. Charges for entertainment were high. On the first trip near Tensaw he paid $1.50 for a night’s lodging, and now at Hawkins’ eleven shillings, “although not worth the half.”

Later his wife, Peggy Dow, recounts a similar trip east by way of the Bigbee settlement in December but does not give the year. It was Lorenzo’s tenth passage, however, to and from Natchez.

There seems to have been an Indian path, crossing a slough called a “Hell Hole,” and they went over a river by night. They “staid two or three days in the St. Stephens neighborhood,” and she notes “the Tombigbee there as beautiful, with water clear as crystal. St. Stephens was small but made a handsome appearance.” They crossed by a ferry and in a day and a half passed over the Alabama too, a beautiful river, “almost beyond description.” This was probably at or near what is now Claiborne.

They then struck the road cut by order of the president from Georgia to Fort Stoddard (sic.) They frequently met people on it removing to the Tombigbee and other parts of Mississippi Territory. The road having been newly cutout, the fresh marked trees served for a guide; there was a moon but it was shut by clouds.

The troubles of immigrants on these routes can well be pictured from the journal of Rev. John Owen, describing the removal of his family in 1818 by wagon from near Norfolk, Virginia, to Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The roads in old settled Virginia he declares bad enough, but, after he passed through Beauford’s Gap of the Alleghanies and descended the Holston Valley via Knoxville, sickness, upsets, breakages and discouragements were their daily experience. Even before he reached East Tennessee he wished that he had not been born.

Between “infernal roads” and straying horses, he declared “the Devil turned loose” in good earnest. He seems to have gone down the Sequatchee Valley to the Tennessee River. Exactly where he crossed into Alabama Territory in the Cherokee boundaries does not appear, and the only definite point named in the eight days between there and his destination is Jones’ Valley, near modern Birmingham. Possibly he crossed at Nickajack and from the Georgia road went down Wills’ Valley, along the route of the present Alabama Great Southern Railroad.

In Alabama he found the smiths lazy, meal scarce, corn and fodder high, and people rough and “shuffling,” but he does make one of his few entries of “roads good,” and he does not mention as many accidents at this end of his route as before crossing our line. Maybe he had become used to them. The day after Christmas he makes the entry, “past broken roads and got to Tuscaloosa and feel thankful to kind Heaven that after nine weeks’ traveling and exposed to every danger that we arrived safe and in good health.”

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS – Settlement:: Lost & Forgotten Stories (Volume 2)

Alabama Footprints: Settlement is a collection of lost and forgotten stories of the first surveyors, traders, and early settlements of what would become the future state of Alabama.

Read about:

- A Russian princess settling in early Alabama

- How the early settlers traveled to Alabama and the risks they took

- A ruse that saved immigrants lives while traveling through Native American Territory

- Alliances formed with the Native Americans

- How an independent republic, separate from the United States was almost formed in Alabama