UNION LEAGUE OF AMERICA

(This has been transcribed verbatim from: History of Alabama and dictionary of Alabama biography, Volume 2 By Thomas McAdory Owen, Marie Bankhead Owen – Please remember the time period and be aware of offensive language)

UNION LEAGUE OF AMERICA is a secret political society, which originated in the Northern States in the latter part of 1862, whose members were pledged to uncompromising and unconditional loyalty to the Union, and to the repudiation of any belief in State rights. The objects of the league were “to preserve liberty and the Union of the United States of America; to maintain the Constitution thereof and the supremacy of the laws; to sustain the Government and assist in putting down its enemies; to protect, strengthen, and defend all loyal men, without regard to sect, condition or race; and to elect honest and reliable Union men to all offices of profit or trust in National, State, and local government; and to secure equal civil and political rights to all men under the Government”

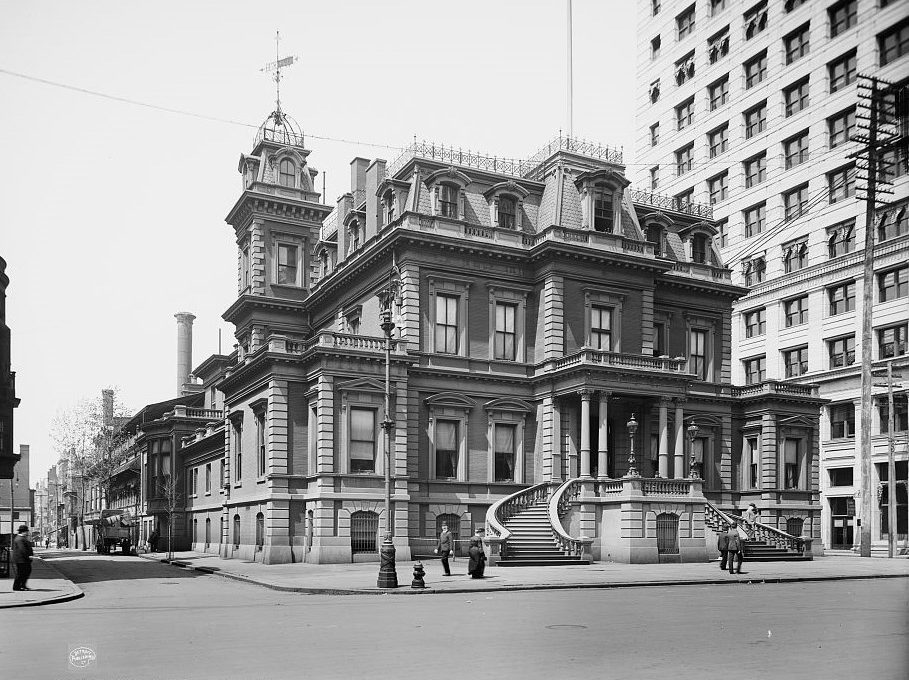

The movement which crystallized in the organization of the Union League originated among the attaches of the United States Sanitary Commission, and the first local league is believed to have been organized in Ohio, in September, 1862. In December of the same year, the Philadelphia Union League was organized, and it was followed, in January, 1863, by the New York Union League Club. Within a few months, similar leagues or clubs had been installed in nearly every part of the North.

Alabama State Council

The constitution of the National Council of the Union League of America provided that the organization should consist of a national council, one council for each State, Territory and the District of Columbia, “and of such subordinate councils as may by them be established .” The national council was composed of representatives elected by the several state, territorial, and district councils, and it had general superintendence of the league.

The constitution adopted by the Alabama State Council, which doubtless was the same as or very similar to those of the other state councils, set forth the object of the league in language identical with that of the general constitution; and provided that the state council .should have “the general superintendence of the league throughout the State, with power to make all rules, regulations and orders necessary to effect the designs of the league, provided the same do not conflict with this constitution or the constitution of the national council.”

The officers were a president, first and second vice presidents, recording and corresponding secretaries, chaplain, treasurer, marshal, sergeant at arms, and an executive committee. For “Qualifications for Membership,” it was provided that “All loyal citizens of the age of eighteen years and upward are eligible for membership in the League; also aliens who have declared their intention to become citizens. No member of this League shall be absolved from the obligations imposed in its ritual.” Attached to the constitution and forming a part of it, was a group of seven “Instructions to Deputies,” one of which directed them to “instruct the councils that they should hold their meetings once in each week, and that they should follow the ceremony as nearly as possible. Advise them to enlist all loyal talent in their neighborhood, and that they have speakers whenever they can.”

The Union League entered Alabama before the close of the War, probably in the first part of 1864. Local leagues are known to have been established in Huntsville, Athens, Florence, and probably elsewhere in northern Alabama, as early as the spring of 1865.

When it first entered the State, the league was thought to be an organization of respectable northern men of union sentiments, and quite a number of substantial citizens of north Alabama joined. However, comparatively few native white “Unionists” were admitted during the first few months of the league’s existence, as the members from the North and those who belonged to the Union Army did not care to associate with them more than was necessary.

Later, natives were quite freely admitted, and still later, the membership was made up more and more of negroes. As the number of negro members increased, the better class of white members withdrew, until the membership of the league, particularly in the counties where the negro population was in excess of the white, was made up almost wholly of the blacks. The proportion of white to negro members of the league has been variously estimated, but accurate figures are not accessible; neither is the total of its members at any time on record.

Within a few months after its entrance into the State, there was a league in nearly every community of north Alabama, and within a comparatively short time, the membership was made up almost wholly of negroes, with a few carpetbaggers and scalawags who controlled and trained them for their political duties.

The conduct of the leaguers was frequently such as to create the impression among the respectable citizens that they were banded together, not so much for political purposes, as to commit depredations upon the white people. Meetings were usually held in negro churches or schoolhouses, nearly always at night, and when returning from them the negroes generally made raids upon the livestock, poultry, fields and gardens of the whites.

Sometimes they stopped in front of the homes of white men who had incurred their dislike, and made threats against them, firing volleys to awaken and intimidate. The league at Tuscumbia received instructions from Memphis to use the torch. Arrangements were made to carry out the instructions and burn the whole town.

Upon the night selected for the burning they met and divided themselves into squads, “three for an advance guard, three to carry the coal-oil and matches, and the balance to remain behind. . . .” However, first one negro and then another suggested that this or that white man was a good man, and at last it was agreed that only the girls’ school building should be burned. Several of the perpetrators of this deed were caught and summarily dealt with by the Ku Klux Klan.

Membership and Methods

In securing new members for the league, systematic canvasses were made from plantation to plantation in nearly every county in the northern part of Alabama. It was testified before the Congressional Ku Klux Committee that boys 15 years of age were eligible for membership. The chief attraction of the league to the negroes was its secret work. Its elaborate ritual, designed to impress the superstitious and illiterate mind, was prepared in the North for the use of the leagues in the South. No such rituals were used among the intelligent members in the Northern States. The most prominent feature of the proceedings was the administering to initiates of the most solemn oath of secrecy. An equally solemn oath to carry out the instructions of the officers of the league was taken by every candidate, and drastic punishment was visited upon violators of this oath. Testimony was elicited by the Ku Klux Committee to the effect that in some cases traitors to the league were put to death.

Political Activities

The prime object of the Union League was to control the suffrage of the freedmen. No one was admitted to membership who would not first agree to vote none but the Republican ticket. Soon after its establishment, the league began to select candidates for nearly all the offices, and took active steps to see that its members carried out their pledge. Arrangements were made at polling places to have representatives of the league examine the ballot of every negro who presented himself, and they did not hesitate to substitute a Republican for a Democratic ballot. In the beginning, the negroes seemed to be more concerned about the prospective division of confiscated property than in politics; but as it became apparent that there would be little property to divide among them, they took more interest in politics and in the assertion of their rights. The teachings of the carpetbagger leaders of the league soon began to bear fruit in an increasing insolence and a more defiant attitude of the blacks toward the whites. Stealing increased proportionately. The league was really a political machine to further the interests of the national Radical party.

These facts appear from a document, in the Alabama department of archives and history, which was widely circulated among the negroes of the South in 1867-8, by the Union Republican Congressional Committee at Washington, through the league, entitled “The Position of the Republican and Democratic Parties—a dialogue between a white Republican and a colored citizen. . . .” This document was popularly known as the “Loyal League Catechism,” and was intended to convince the freedmen that the Radicals and the Republicans were “one and the same party,” and that the members were “all in favor of freedom and universal justice,” and all desirous “that slavery should be abolished, that every disability connected therewith should be obliterated, not only from the national laws but from these of every State in the Union.” In answer to the question, “Why cannot colored men support the Democratic party?” the “catechism” stated. “Because that party would disfranchise them, and, if possible, return them to slavery and certainly keep them in an inferior position before the law.”

In April, 1867, the “Alabama Grand Council of the Union League of America” adopted a set of six resolutions, in the course of which it was declared, among other things, “that we hail with joy the recurrence to the fundamental principle. . . . ‘that all men are created equal;’ that we welcome its renewed proclamation as a measure of simple justice to a faithful and patriotic class of our fellow-men, and that we firmly believe that there could be no lasting pacification of the country under any system which denied to a large class of our population that hold upon the laws which is given by the ballot.” It was further stated “that we consider willingness to elevate to power the men who preserved unswerving adherence to the Government during the war as the best test of sincerity in professions for the future;” and “that if the pacification now proposed by Congress be not accepted in good faith by those who staked and forfeited ‘their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor’ in rebellion, it will be the duty of Congress to enforce that forfeiture by the confiscation of the lands, at least, of such a stiff-necked and rebellious people;” and, what was the kernel of the whole matter, “that the assertion that there are not enough intelligent loyal men in Alabama to administer the government [to hold the offices] is false in fact, and mainly promulgated by those who aim to keep treason respectable by retaining power in the hands of its friends and votaries.”

Cause of Organization of Ku Klux Klan

While the activities of the Freedmen’s Bureau stirred up strife between the races and increased misunderstandings and friction in all dealings between whites and blacks, the Union League, or “Loyal League,” as it was popularly known, was the chief disorganizing factor, and to its activities more than to any other cause was due the organization of the Ku Klux Klan. It was not until southern men realized that nearly all the negroes were banded in a secret, oath-bound league, under the direction and control of alien and Irresponsible politicians, against the white people of the South, that they began to cast about for some practicable method of frustrating their designs. The loyal leaguers threatened to burn and massacre, and the whites believed that they might carry out their threats. The Ku Klux Klan was organized primarily for the protection of the homes and families of its members and all other respectable people, and it was only incidentally and as a result of the political activity of the loyal league, that the Ku Klux took on a political character. It was testified before the Ku Klux Committee even by Radical witnesses that the clan was generally understood to have been organized to counteract the influence of the loyal league.

Decline of the League

After the election of 1868, the league was not active except in the larger towns. During 1869, many of the councils were transformed into clubs which took no active part in political contests. The Ku Klux Klan undoubtedly was the principal cause of the decline of the league. In the election of 1870, the Radical leaders missed the solid support furnished by the league in previous elections, and sent out urgent appeals from headquarters in New York for its reestablishment to assist in carrying the national election. No definite date for the final disappearance of local leagues from the State can be fixed.

SOURCE

History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography, Vol II, Thomas McAdory Owen, 1921, S. J. Clarke Publishing Company.

References – Committee on affairs in the insurrectionary States, Report on Ku Klux conspiracy, Alabama testimony (H. Rept. 22, 42d Cong., 2d sess.), passim; Fleming, Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama (1905), pp. 553-568; and Documentary history of Reconstruction (1907, vol. 2, pp. 3-29; and “Union League documents” inWest Virginia VnU versity documents relating to Reconstruction (1904); and “Formation of the Union League in Alabama,” in Gulf States Historical Magazine, Sept. 1903, pp. 74-89; Herbert, Why the Solid SouthT (1890), pp. 41-45; Damar, When the Ku Klux rode (1912), pp. 47-50; Lester and Wilson, Ku Klux Klan (Fleming ed., 1905), pp. 77-82; Miller, Alabama (1901), pp. 246-248; “Ritual of the Union League,” in Montgomery Advertiser, July 24, 1867.

ALABAMA REVOLUTIONARY WAR SOLDIERS VOLUME II

After

the Revolutionary War, free bounty land was offered by the federal

government to citizens and soldiers for their service.

This

book is the 2nd Volume in a series of books which includes

genealogical and biographical information on some Revolutionary

Soldiers who were in early Alabama and/or collected military pensions

for their service. Some of their descendants still remain on the

bounty land they received. The soldiers in this volume include: JACOB

HOLLAND, CHARLES M. HOLLAND, THOMAS HOLLAND, COL. JOSEPH HUGHES,

CHARLES HOOKS, DIXON HALL, BOLLING HALL, WALTER JACKSON, WILLIAM

HEARNE, THOMAS HAMILTON, GEN. JOHN ARCHER ELMORE, REVEREND ROBERT

CUNNINGHAM, JAMES COLLIER, THOMAS BRADFORD, REUBEN BLANKENSHIP, HENRY

BLANKENSHIP, DANIEL BLANKENSHIP with a special story about the

patriotism of CHARLES HOOKS sister…MARY HOOKS SLOCUMB