Patron+ member story

(Transcribed excerpt from HISTORY OF JACKSON COUNTY, ALABAMA

by John Robert Kennamer, Decatur, Al 1935:

Condensed by Josephine Lindsay Bass on July 26, 1996

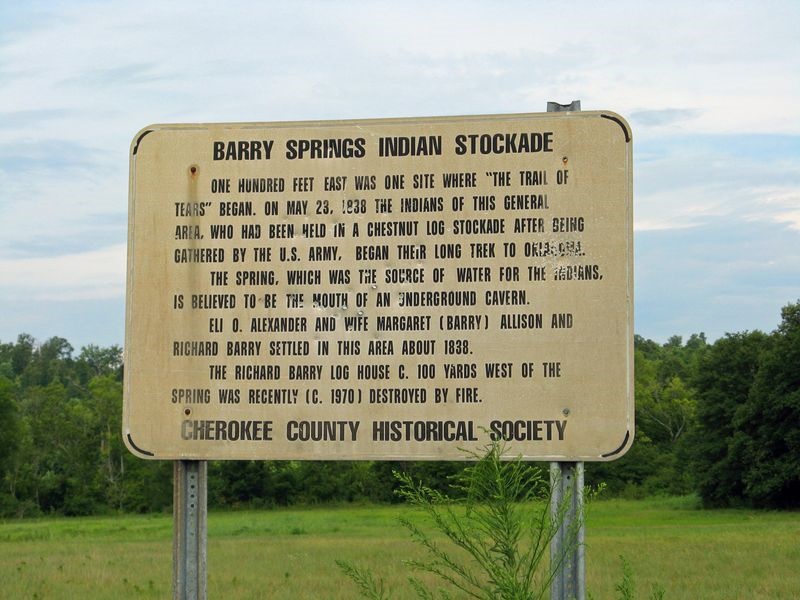

Congress had passed a law in 1834, providing for the removal of the Cherokees in Alabama, Tennessee, and Georgia, to the Indian Territory. Chief John Ross opposed the removal West and refused to sign the treaty. In 1837-38 their removal from their native home furnished one of the touching and most pathetic stories in American history.

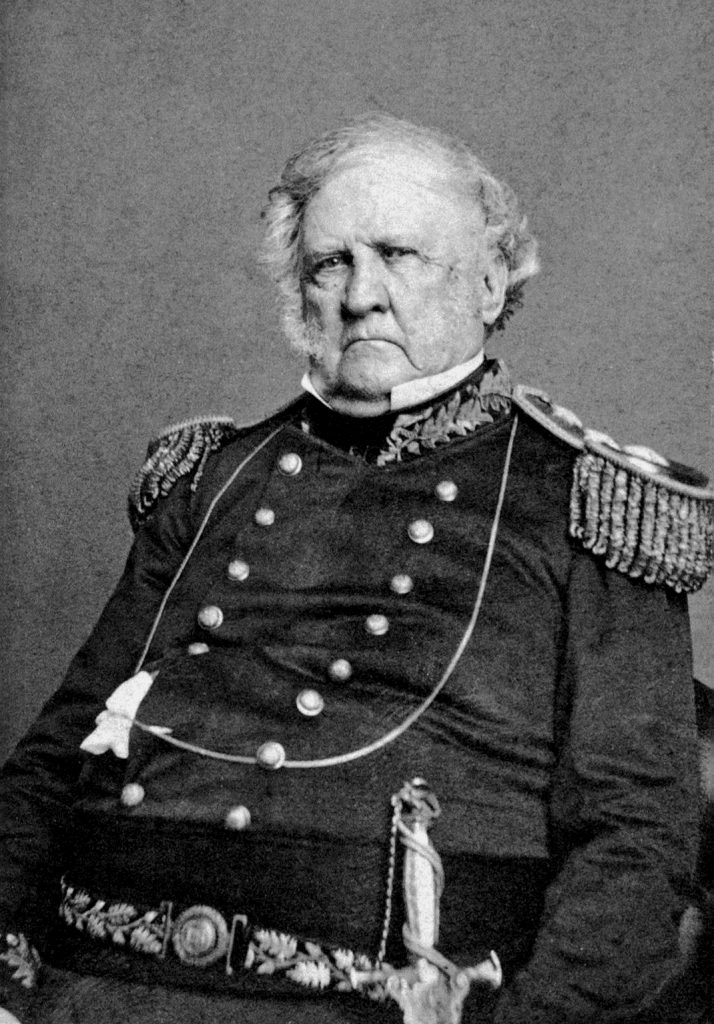

General Winfield Scott divided Indians into camps for removal

General Winfield Scott was commander of the military forces. His troops entered the territory of the Cherokees and divided into small parties for the purpose of searching every home. They were placed in camps or palisades enclosed by stakes set in the ground and pointed at the top as a fence. Many Indians died in these camps where as many as 5,000 were assembled at a time. One out of every seven died before reaching his new home in the West.

Three ports of embarkation

There were three ports of embarkation of those who went by water: Charleston on the Hiwassee River, Ross’ Landing (now Chattanooga), and Gunter’s Landing on the Tennessee. One such detachment noted in Dr. C. Sillybright’s journal relates that they left Ross’ Landing, March 3, 1837, in eleven flatboats. This fleet of flatboats was met at Gunter’s Landing by the steamer Knoxville, which took charge of the boats and guided them to Decatur, Alabama. From Decatur, a portage was made around Muscle Shoals to Tuscumbia in railroad cars. There the emigrants were met by the steamer Revenue with a flotilla of keels. On March 27 these emigrants were unloaded at a point just beyond Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Chief John Ross moved his people himself

Chief John Ross got an agreement with Gen. Scott to move his people himself. He marched more than 10,000 overland in separate bands and in different routes in order to be assured of finding a supply of water and game for food on the way. The season had been so dry the marchers suffered untold privations, and sixteen hundred perished en route. Ross’ wife, who had gone on the boat, Victoria, died on the way and was buried at Little Rock, Arkansas.

Alexander Reid, and Jonathan Beeson of Paint Rock Valley; William Sims, Samuel Hill, and Nathan Kennamer and other citizens of the county served in the army which removed these Indians.

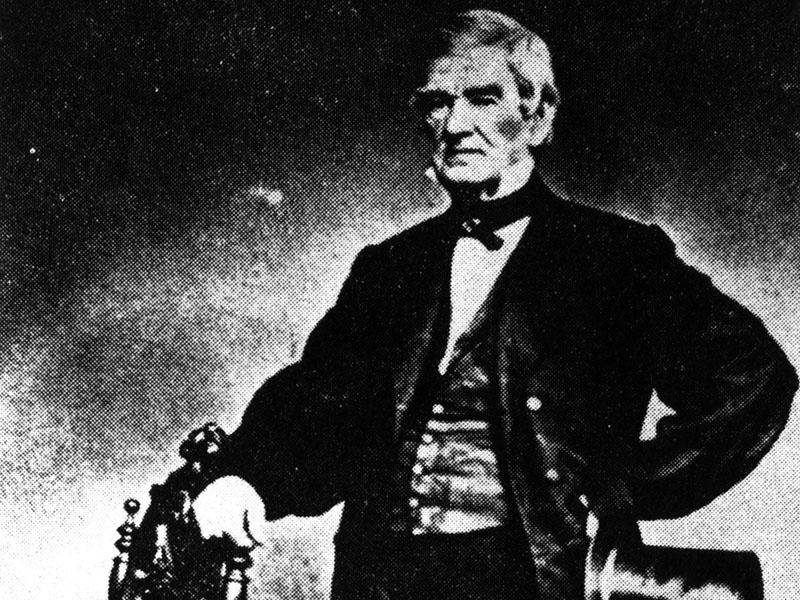

John Ross, Cherokee chief

According to Cherokee Connections by Myra Vanderpool Cormley, 1995, “The removal actually started when about 17,000 Cherokees, who had refused to emigrate under the disputed Treaty of New Echota (1835), were rounded up at gun or bayonet point by soldiers and were placed into holding areas, which were guarded. It is these stories of the harsh roundup that have become interwoven with the actual removal on the Trail of Tears.

Removal in June of 1838

Early in June of 1838, the removal to what would later be Oklahoma started when approximately 2,800 of those who had been forcibly rounded up, were divided into three detachments, each accompanied by a military officer, a corps of assistants and two physicians. The first detachment of about 800 – made up of Cherokees from Georgia who had been concentrated at Ross’s Landing (now Chattanooga) – departed 6 June. It was forcibly placed on boats and was under the command of Lt. Edward Deas.

The second group, number about 875, left 13 June. It was under the command of Lt. R. H. K. Whiteley, with five assistant conductors, two physicians, three interpreters and a hospital attendant. The third contingent of 1,070 departed from Ross’s Landing 17 June in wagons and on foot for Waterloo, Alabama, where they were to be transported on Flatboats. After their departure, they learned that the removal of the remaining 13,000 Cherokees had been suspended until autumn because of the heat, drought, and sickness. This third group asked to be allowed to return and remain with others in Tennessee, but their request was denied.

Chief John Ross persuaded Gen. Scott to wait

Major General Winfield Scott was in charge of the 7,000 federal and state troops whose job it was to round up and eject the Cherokees from their country in Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee and North Carolina.

Major General Winfield Scott

Returned to the Cherokee nation

In the early part of July in 1838, when Chief John Ross returned to the Cherokee Nation from the nation’s capital, where he had been negotiating unsuccessfully about the treaty and removal, he was able to persuade General Scott to permit the Cherokees to manage and control their own removal in the autumn. Thus, Ross gained a concession that was not granted to any other tribe that was removed, and as a result, the great majority of Cherokees who traveled the Trail of Tears were not guarded by the soldiers.

Divided into 13 detachments

The Cherokees were divided into 13 detachments averaging 1,000 each. Officers were appointed by the Cherokee council to take charge of the emigration, with two leaders in charge of each detachment and a sufficient number of wagons and horses for the purposes. To maintain order on the march each party established a quasi-police organization that punished infractions of regulations. They also had guides and provisioners to arrange for their food. They finally started west after the drought was broken in October of 1838.

Some refused to emigrate

However, there was a party of Cherokees that belonged to the treaty faction (pro-removal) of the tribe who refused to emigrate under the leadership of Chief Ross. This group left the old nation on 11 October under the direction of Lt. Edward Deas. Under the Treaty of New Echota, the Cherokees were assured that once they were settled in their new land in Indian Territory they would:

Have their firearms restored to them once they were at or beyond the Mississippi River;

Be paid for their improvements that they had left in the east;

Be paid for their lost land;

Be paid subsistence for six months to one year.

Almost one-quarter of all Cherokees had white ancestors

Most of them went with their families and friends to Indian Territory, and only four of the 17 contingents had U. S. Army escorts. It is estimated that about 4,000 Cherokees died from the time of the roundup until they reached what is now Oklahoma.

It is claimed that by 1830 almost one-quarter of all Cherokees had some white ancestors, with two out of three intermarriages involving a white man and a Cherokee woman. These white ancestors usually will turn out to be traders, missionaries, teachers or government agents. Intermarriage with blacks was rare, and after 1824, it was against Cherokee law.

Black slaves traveled with their masters

Among the Cherokees who traveled the Trail of Tears were about 1,600 black slaves who were pushed westward along with their masters. After the Civil War most of these freed blacks remained in Indian Territory, and by and large remained in the nation in which they had lived as slaves. Race was a significant factor with the Cherokees, and it can be most difficult to prove a mixed Cherokee-African American bloodline. In such cases, the Cherokee bloodline was frequently discounted at the time of the official enrollment.”

I recently gave you $25…..Now you want $2 more ….Quite frankly I do not understand WHY I can’t view all your articles….

Hi Phil,

You gave $25 through the Alabama Pioneers Paypal Donation. Paypal Donations are strictly donations to the Alabama Pioneers website. It is for people who just want to give a one-time donation to the Alabama Pioneers website.

The Patreon Program is a separate program entirely run by Patreon.com This link should explain it in more detail. http://www.alabamapioneers.com/did-you-know-we-now-have-an-interactive-level-on-alabama-pioneers/

There is no way the two programs can be mixed.

If you want, I can refund your $25 via Paypal and you can join the Patreon program instead.